By Elliott Brack

Editor and Publisher, GwinnettForum

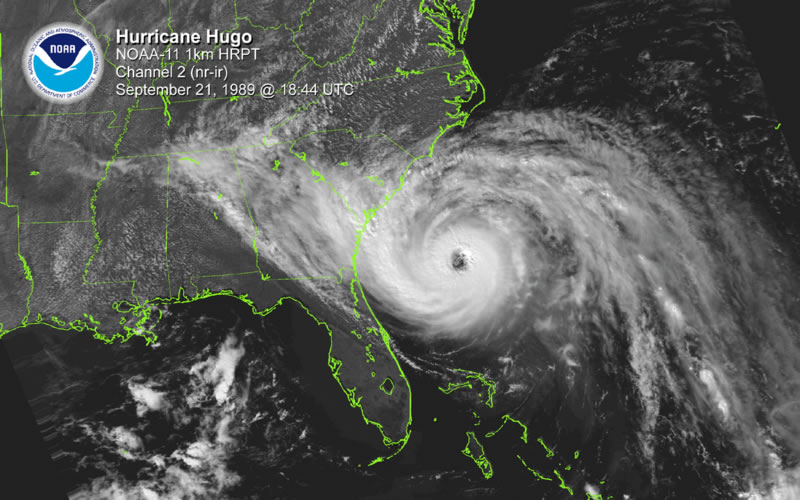

OCT. 1, 2024 | Hurricane Hugo came ashore at Sullivan’s Island near Charleston, S.C. on Sept. 22, 1989, one of the most destructive hurricanes to hit the Atlantic Coast.

![]() A few weeks later, I flew Delta to Charleston. Approaching the city, from the air the destruction was so vast that you wondered how anyone could survive such an onslaught. Homes were destroyed in many places. Obviously, power lines and trees were scattered at random. It was awful. The storm caused 22 deaths in the United States.

A few weeks later, I flew Delta to Charleston. Approaching the city, from the air the destruction was so vast that you wondered how anyone could survive such an onslaught. Homes were destroyed in many places. Obviously, power lines and trees were scattered at random. It was awful. The storm caused 22 deaths in the United States.

Last week, Hurricane Helene rampaged through Florida, Georgia, South and North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky, destroying much in its path. More than 100 people are dead, at least 25 in South Carolina, 25 in Georgia, 42 in North Carolina, and probably more in other states. Disclosure of more deaths can be expected.

Families have been ripped apart. And it’ll take months for the clean-up. Some destroyed towns may never be rebuilt. Tourism in the Appalachian states will suffer. Western North Carolina roads are closed, and bridges destroyed. It will take months to replace these facilities. Helene may exceed the damage Hurricane Katrina caused in 2005, which destroyed 800,000 homes and caused over $160 billion in damage.

Yet out of this vast obliteration, mankind will find ways to survive, and even improve. We certainly saw that in Charleston after Hurricane Hugo.

Once Charleston started recovering, it realized that the storm’s winds and water damaged or destroyed many of the Lowcountry’s historic buildings. It left much of Charleston’s iron, plaster and fine wood work in disrepair. Property owners and stewards of historic civic buildings had to search as far away as Europe to find professionals with the skills needed to repair the damage, since there were not enough skilled artisans in the United States to meet the demand for repairs and restoration of these historic buildings.

In response to this gap, a group of Charleston leaders planted the seeds that led to the founding of the American College of the Building Arts (ACBA) in 1999. Classes were offered at several different locations in and around the city of Charleston, including the city’s iconic Old District Jail, which became the college’s primary location for 17 years.

In 2004, the college was licensed to recruit students for the four-year Bachelor of Applied Science degree and two-year Associate of Applied Science program. Students take regular college classes in the morning, and then work with the world-famed skill artisans in the afternoon. Its graduates land jobs around the world, and are employed at places like the Smithsonian Institution, Library of Congress and as skilled artisans in Europe.

In 2009, Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Colby M. Broadwater became president and reorganized the college, since it was losing money. Initially, he cut the budget by 50 percent, with such items as eliminating individual secretaries for its professors. Today, the college is well-financed and sound. In 2015, it began operations in the Old Trolley Barn on Upper Meeting Street, a remodeled facility beautifully enhanced by the work of its students.

A walk through the ACBA shows students working in stone carving, plaster, architectural carpentry, ironworking, blacksmithing and classical architecture. The quality of their work is amazing. The college currently enrolls about 150 students.

It’s a stretch after a hurricane to find something positive. But Charleston founded the only building arts school in the country after Hugo.

We anticipate and pray that something good can come out of Helene.

- Have a comment? Click here to send an email.

Follow Us