By Elliott Brack

Editor and Publisher, GwinnettForum

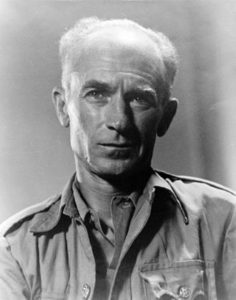

FEB. 1, 2022 | During World War II, one of our nation’s most respected journalists was Ernie Pyle, a Washington editor who became a war correspondent. His reporting from London, Africa, Italy and France was syndicated in newspapers all across the country.

![]() Pyle reported about ordinary American soldiers during World War II. Before the war, he was a roving human-interest reporter from 1935 through 1941 for the Scripps-Howard newspaper syndicate that earned him wide acclaim for his simple accounts of ordinary people across North America. During the war, he talked to the guys in the trenches. One GI described his articles this way: “He catches the spirit. Nothing phony in it anywhere.”

Pyle reported about ordinary American soldiers during World War II. Before the war, he was a roving human-interest reporter from 1935 through 1941 for the Scripps-Howard newspaper syndicate that earned him wide acclaim for his simple accounts of ordinary people across North America. During the war, he talked to the guys in the trenches. One GI described his articles this way: “He catches the spirit. Nothing phony in it anywhere.”

His dispatches from the war were run in newspapers across the country. His impact was such that the Pulitzer Prize committee suggested his editor submit his stories for consideration in the prize. His editor was delighted, mainly because he had never heard of the committee soliciting a submission. The prize was for “….distinguished war correspondence during the year 1943” covering the war in Europe.

Later these daily dispatches were put together in a book, entitled Brave Men. In his dispatches back to the states, Pyle would identify soldiers from larger cities in a way that confused me. Pyle wrote in this manner: “Sergeant Sam Smith, of 214 Fourth Street in Dallas, Tex……” giving not just the person’s name, but also his exact home address. For smaller places, he simply named that town.

For me, seeing such detailed addresses throughout the book was frustrating. It seemed like an unusual way to report. “Just tell me it was the Sam Smith from Dallas would be enough,” I remember saying to myself.

Later on in the book, I was startled to read on page 425 this passage: “(He) was a smiling, tall young fellow, with clipped hair, Dallas Hudgens from Stonewall, Georgia. He was feeling stuffed as a pig, for he’d just got a big ham from home and had been having at it with vengeance.”

What? It was the first time I had ever read a book where the author was writing about someone I knew. That was Dallas Scott Hudgens, the Duluth developer. That startled me.

Later on, when talking with Scott about being in the book, an understanding hit me, as Scott told me: “Yeah, he was writing about me and our squad. When his comments appeared in the newspaper column, my mother got mail from all over the United States, enclosing that clipping. Other people far away wanted to make sure she had seen it, and wanted her to know that Pyle had run across me in the war. He caught up with us near Cherbourg, France, a few days after D Day.”

“My mother had mailed me a canned ham, and when the ham caught up with our five man crew, we were enjoying the ham when Pyle arrived. We offered some to Pyle, and he enjoyed it, too.”

But Pyle, we finally understood, was doing more than we realized with his address style. In effect, Pyle was getting around the censors, not passing on something vital to our enemy, but telling Mrs. Hudgens (and other mothers across the nation) that their sons were OK.

It was an ingenuous way to report on the war, making parents and friends happy to know their loved one was all right. No wonder Pyle won the Pulitzer.

- Have a comment? Send to: elliott@brack.net

Follow Us